Learning 4a Change is a collaborative inquiry into the nature of learning in and for the Anthropocene transition.

This introduction is offered as a starting point to be refined, elaborated, challenged or abandoned in favour of alternative approaches to reinventing our learning practices in an acutely unfamiliar and challenging context.

To post on this blog you need to register as a contributor

CLICK HERE TO REGISTER AS A CONTRIBUTOR

DISCUSSION PAPER:

Learning 4a Change :

a collaborative inquiry

2016-07-05

“The point is not to think outside the box but to recognise that the box itself has moved, and in the 21st century will continue to move increasingly rapidly”

Timothy Seastedt, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 2008

The Anthropocene transition can be understood as a shift from a prevailing cultural space to a new one appropriate for the continuing evolution of human societies in symbiotic relationship to the Earth. Such a historical transition can be likened to the shift from the Medieval worldview to the Renaissance.

The Anthropocene transition can be understood as a shift from a prevailing cultural space to a new one appropriate for the continuing evolution of human societies in symbiotic relationship to the Earth. Such a historical transition can be likened to the shift from the Medieval worldview to the Renaissance.

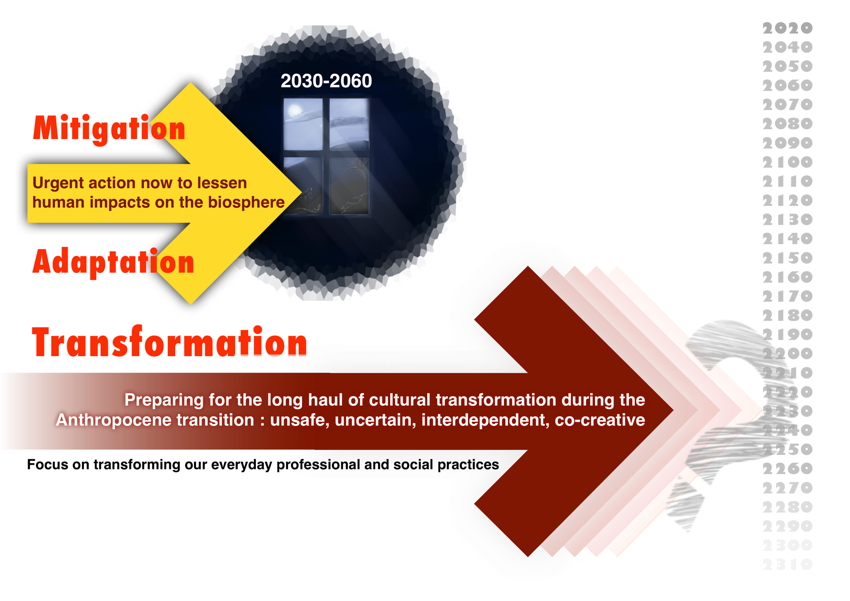

The Anthropocene transition is likely to extend over multiple generations and its ultimate outcome is unknowable. It is conditioned by a new geological/biophysical epoch in which human impacts on the Earth System have become connected and systemic, driving changes that humanity neither controls nor can predict. The consequences will be irreversible and likely to persist for thousands of years. Four words capture the character of this age: unsafe, uncertain, interdependent, and co-creative.

To successfully navigate a period of existential danger towards a viable future, we must reconceptualise our professional and social practices within a framework of radically different cultural values. This will involve continuous and rapid adaptive learning – the challenge of learning in and for the Anthropocene transition.

The red threads of Anthropocene learning

So what are the “red threads” that might inform the design of our learning processes and institutions, both formal and informal, individual and collective?

The purpose of this short paper is to suggest a framework that defines a space for inquiry. Our aim is to reconceptualise our approach to learning in and for the Anthropocene.

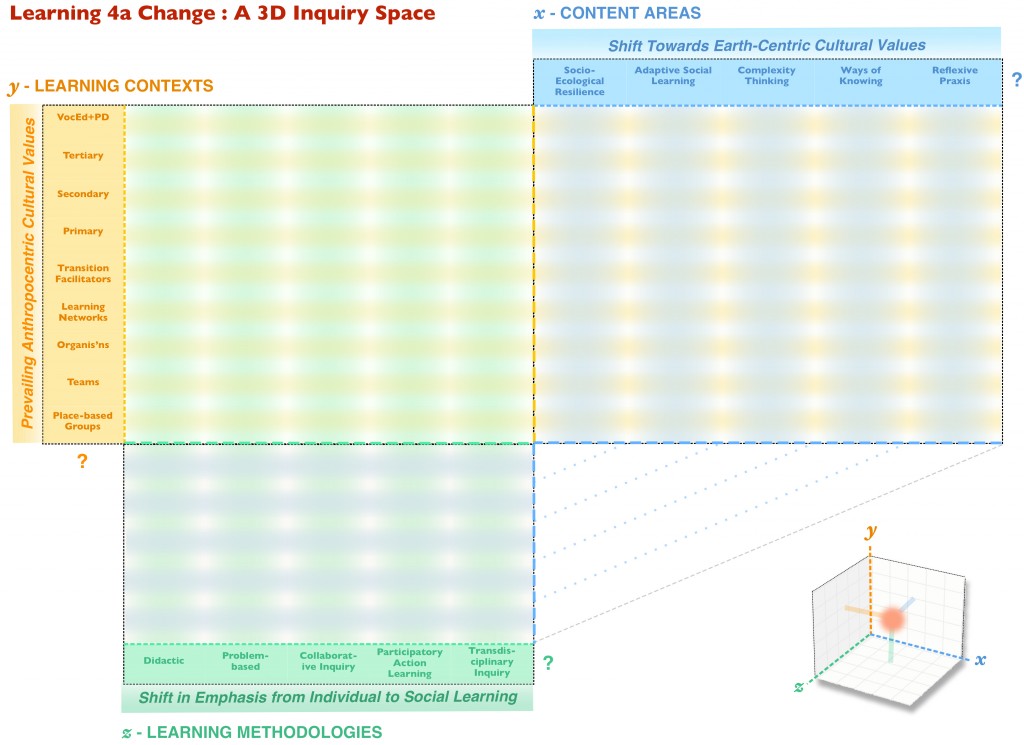

It proposes a necessarily fluid inquiry space defined by three dimensions:

- Content Areas

- Learning Contexts

- Learning Methodologies

The inquiry space it suggests should be imagined as a fuzzy three dimensional field described by the dynamic interplay of content, context and methodology. This suggested framework or matrix should be approached as a thought experiment to help us explore possible learning imperatives for an age of uncertainty and systemic disruption. It invites critique and revision at a meta level, of its structure, and in its specifics. It is offered as a starting point for conversation – a provocation for a rethinking of our learning practices.

x axis – Content Areas

The proposed content areas are the determining dimension of this 3D matrix. They point to key areas of capability necessary for the tasks of social and systemic redesign and cultural renewal.

Socio-Ecological Resilience

Resilience is the capacity of a system to absorb disruption and reorganise itself under conditions of turbulence and on-going change. Socio-ecological resilience must be a core organising principle for the Anthropocene transition. It establishes eco-systemic integrity as a fundamental design criterion for human technologies, economies, habitats and systems of governance.

Socio-ecological resilience focusses attention on the critical relationship between human systems and the eco-systems in which they are embedded and on whose vitality they ultimately depend. Within this context it values the preservation, enhancement, and fundamental unity of culture and ‘nature’ and favours distributed networked technologies and systems with localised capability and control instead of centralised, inflexible systems that are inherently slow to adapt.

Understanding the principles of socio-ecological resilience and building capacity for their practical application is essential in times of systemic disruption and unexpected change.

Adaptive Social Learning

Ultimately our ability to survive and thrive in a period of radical uncertainty and profound change will depend on our capacity for wise collective action reflecting a new consciousness of our place in the Earth system. Consider the full implications for learning of those three key descriptors: wise, collective, action.

Facilitating the emergence of this new cultural awareness requires a greatly enhanced capacity for adaptive social learning — groups of people sharing their experiences in action, experimenting with different ways of dealing with common challenges, reflecting together on the meaning of their experiences, and deciding on new forms of co-operative action.

Building adaptive learning capability into all our collective formations from campaigns to communities, businesses to bureaucracies, networks to nations is fundamental to our ability to co-create a viable future.

Complexity Thinking

Understanding that socio-ecological systems are based on a complex, dynamic and unpredictable web of connections and interdependencies is the first step towards transformative professional and social practices.

Complexity is not a synonym for complicated. It refers to a system in which many independent entities interact in ways that are difficult (or impossible) to predict but give rise to new higher order patterns of behaviour or organisation. This spontaneous organisation is referred to as emergence and is a function of the dense interconnections between the entities that make up the system. Examples of complex adaptive systems (CAS) are stock markets, immune systems, animal brains, ecosystems and human socities.

Our learning culture must support experimentation with new models for socio-ecological systems that make it possible for us to understand human activity within an ecological context. And we need a more dynamic view of systemic change embracing concepts like emergence or self-organisation. Complexity thinking offers a new paradigm that defines a fundamentally different relationship between ecologies, societies, technologies, economies and systems of governance.

Experimentation and learning through adaptive and collaborative professional and social practices informed by complexity thinking fosters intelligent change in socio-ecological systems. It ensures that different types and sources of knowledge are valued and considered when developing solutions, and leads to greater willingness to experiment and take risks.

Ways of Knowing

The shift from predominantly Western mechanistic and reductionist modes of knowing to a more holistic, multidimensional worldview underpins the cultural transformation the Anthropocene demands. Holism is an epistemic principle that emphasises the intrinsic coherence of complex systems and their emergent properties that cannot be understood from a knowledge of their parts. It implies that the system as a whole determines in important ways how the parts behave, even while the parts condition the nature of the whole.

As an approach to inquiry and learning, holism does not displace other modes of knowing but transcends them and opens the door to a more creative engagement with change in complex systems at all levels from the micro-organic to the planetary.

There are many ways of knowing the world, each with their own deep understandings and associated cultural practices. Respect for this rich plurality will help dispel the stupor of a dangerously dysfunctional globalised monoculture. Extant indigenous cultures are often characterised by a holistic, place-based, relational worldview within which humans and nature are seen as one, spirituality is central, sustainability is intrinsic, and Earth-caring is linked to cultural affirmation. Learning to better understand our place within the web of life through a variety of epistemological frames is essential.

Reflective/Reflexive Praxis

Reflective practice is the ability to reflect in and on action to derive new meanings from experience and enable continuous adaptive learning. According to one definition it involves “paying critical attention to the practical values and theories which inform everyday actions, by examining practice reflectively and reflexively” (Gillie Bolton, Reflective Practice, 2010). It is sometimes referred to as “triple loop learning”.

Reflexivity embraces subjective understandings of reality as a basis for thinking more critically about the impact of our individual and collective (i.e. cultural) assumptions, values, and actions on others – both human and other than human. Mindfulness, listening to the whole, and deep listening (or dadirri in indigenous Australian practice) can all be seen as supporting reflexive practice. They involve learners in interrogating both their inner and outer worlds.

Reflexive practice is important to learning in all contexts because it helps us understand how we constitute our realities and identities in relational ways and how we can develop more collaborative and responsive professional and social practices.

y axis – Learning Contexts

The categories suggested on this axis are intended to be indicative rather than definitive. They imply a continuum through place-defined groups, various kinds of teams and intentional groups, organisations and communities, learning networks of purpose, culture or practice, change/learning facilitators, institutional learning settings from primary to tertiary levels, and vocational education and professional development.

Users of the matrix can define the particular contexts within which they are working or have an interest.

z axis – Learning Methodologies

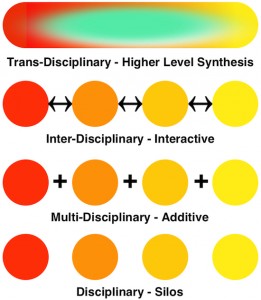

Again this axis represents a continuum on which the five methodologies shown simply represent familiar examples. Of course various methodologies will often be combined in ways appropriate the specific contexts and content. Running through all methodologies there needs to be a commitment to trans-disciplinarity that encourages learners to explore new knowledge syntheses grounded in their empirical observations and experiential reflections.

Again this axis represents a continuum on which the five methodologies shown simply represent familiar examples. Of course various methodologies will often be combined in ways appropriate the specific contexts and content. Running through all methodologies there needs to be a commitment to trans-disciplinarity that encourages learners to explore new knowledge syntheses grounded in their empirical observations and experiential reflections.

Trans-disciplinarity in this context implies the drawing together and integration of knowledge and ways of knowing from diverse disciplines and traditions, including the traditional knowledges of indigenous peoples. It needs to be distinguished from multi-disciplinary approaches that employ the lenses of different disciplines to examine a problem, and interdisciplinary methods that promote a dialogue between disciplines. In simple terms multi-disciplinary denotes additive, inter-disciplinary interactive, and trans-disciplinary holistic.

“It is important to understand … the magnitude of the change required in shaping a viable mode of human presence on planet Earth for the future. All our professions and institutions need to be reinvented in this new context. Eventually this implies rethinking … our role within the planetary process.”

Thomas Berry, The Great Work, 1999